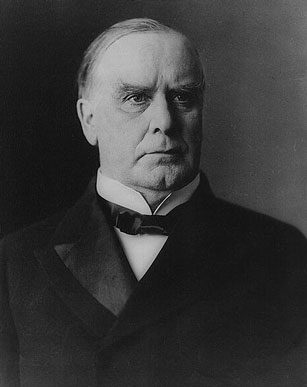

WILLIAM MCKINLEY

Biography

William McKinley was one of the kindliest and most peace-loving of U.S. Presidents. Yet he led the United States at a time when most Americans were determined to go to war. And the life of this gentle and sympathetic man was brought tragically to an end by bullets from an assassin's gun.

Congressman and Governor

In 1876, McKinley was elected, as a Republican, to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was re-elected almost continuously until 1890. In that year the Republicans lost the election because of a tariff—the McKinley Tariff.

In 1890 the business interests of the country were determined to pass a high tariff, or tax on foreign goods, in order to protect American industry from competition. McKinley firmly believed in such a policy, and overcoming all opposition, he got his tariff bill passed. However, resentment over the tariff, especially in the West and South, cost the Republicans heavily in the election, and McKinley lost his seat in Congress.

Undiscouraged by his defeat, McKinley won the governorship of Ohio in 1891. Earlier he had impressed a wealthy Cleveland businessman, who offered to help McKinley further his political career. This businessman was Marcus Alonzo Hanna (1837-1904), one of the most influential men in the Republican Party. A close relationship developed between the two men and grew into a lifelong friendship. Under Mark Hanna's steady direction McKinley would attain the presidency.

In 1892 McKinley was appointed chairman of the Republican National Convention. Some members of his party were so enthusiastic about McKinley that they wanted him to become the Republican presidential candidate. But McKinley felt that he was not yet ready for so important an office. Instead he gave his support to the renomination of President Benjamin Harrison. McKinley's decision not to seek the nomination was a fortunate one. While Harrison was defeated by Grover Cleveland in the election of 1892, McKinley went on to be elected governor of Ohio for a second term.

By 1896, McKinley felt ready to accept his party's nomination for the presidency. At the Republican National Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, he was nominated on the first ballot. The Republicans were confident of victory, for the Democratic administration of President Grover Cleveland had been plagued by an economic depression.

The Campaign of 1896

The Democrats, with William Jennings Bryan as their candidate, campaigned on the issue of “free silver.” Many people, especially farmers in the West, felt their economic hardships would end if the government restored unlimited coinage of silver money. Bryan toured the country urging such a policy. He was a forceful orator, and McKinley was hard pressed to compete with him.

Taking his friend Mark Hanna's advice, McKinley did not try to out-talk Bryan. Instead, he stayed at his home in Canton and conducted a “front-porch” campaign, speaking to groups of people who flocked to his home to listen to him. Businessmen and workers in the East gave him their support, and a good farm crop in the West helped restore prosperity. McKinley received 7,102,246 popular votes to Bryan's 6,492,559 and 271 Electoral votes to Bryan's 176.

President

McKinley's first term of office was an eventful one for the United States. The nation was seething with new growth, and many different interests sought dominance. McKinley seemed ideally suited to the task of harmonizing such clashing interests.

Cuba and the Spanish-American War

The most important event in McKinley's administration resulted from a crisis in Cuba. Revolts by Cubans against Spanish rule had broken out, and the Cubans appealed to the United States for help. Stories of Spanish cruelty toward the Cubans began to arouse American public opinion against Spain. Soon an avalanche of sympathy for Cuba Libre (“Free Cuba”) began to descend on McKinley. The President, above all a man of peace, had already pledged his opposition to any armed interference in another country's affairs. In his annual message to Congress he urged that Spain “be given a reasonable chance”to right the situation. Yet his concern over the plight of the Cuban people was real. He issued a Christmas Eve appeal for public contributions to a Cuban relief fund. And at his initiative over $250,000 of aid was sent to Cuba by the Red Cross.

Early in 1898 two events occurred that left McKinley helpless to avoid war with Spain. The first was a private letter written by the Spanish minister in Washington, D.C. Intercepted by a Cuban, who turned it over to a reporter, the letter was published in American newspapers. In it the minister, De Lorme, called McKinley “a would-be politician…weak and a bidder for the admiration of the crowd…” Though the minister promptly resigned and the Spanish Government apologized, the De Lorme letter turned popular opinion even more strongly against Spain.

Then, a few days later, the United States battleship Maine was blown up in Havana harbor, with a loss of 260 American lives. Newspapers across the country blazed the headline that Spain was responsible and that war was now certain. Actually, no one knows to this day what caused the disaster. But without waiting further, Congress rushed through a bill appropriating $50,000,000 for national defense.

Though McKinley continued to press for peace, Congress and the vast majority of the American public were convinced that war was the only honorable road left open to the United States. A popular newspaper cartoon of the day showed an angry Uncle Sam straining to fight Spain while the President held him back by the coattails. The caption read, “Let go of him, McKinley!”

Soon the President feared that unless he gave way, Congress would declare war over his head. Finally he decided to yield to popular demand, and in April, 1898, war with Spain was declared. Yet McKinley always felt that, left to himself, “I could have concluded an arrangement with the Spanish government under which the Spanish troops would have been withdrawn from Cuba without a war.”

The Spanish-American War lasted less than four months and resulted in a victory for the United States. The United States won control over the former Spanish possessions of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, while Cuba gained its independence.

The Issue of Imperialism

After the war some Americans were undecided as to whether the United States should keep the territory won from Spain. They argued that the United States should not hold on to such possessions as the Philippine Islands, which were far from the country's shores. As the islands of Hawaii had also been acquired during this time, there was a growing fear that the United States was becoming an imperialist power.

McKinley was tormented by his conscience as to what course he should take. Though he felt that the United States had had to interfere in Cuba for “humanity's sake,” he found it hard to justify holding the Philippines. However, others in his party urged him to keep them as legitimate possessions. Finally, after walking “the floor of the White House night after night until midnight,” McKinley decided to accept the islands for the United States.

China and the Open-Door Policy

With major possessions in the Far East, American interest in China and in world politics in general increased. At the time, Great Britain, France, Germany, and Japan were acquiring large “spheres of influence” in China. In 1899, McKinley's secretary of state, John Hay (1838-1905), called on the other powers to allow equality of trade in China. After the unsuccessful Boxer Rebellion in 1900, in which the Chinese revolted against foreign domination, Hay declared that it was American policy to respect the independence of China. He called on the other countries to do the same. This policy of equality of trade with China and respect for its territorial integrity was the basis of the famous Open-Door policy.

The American share of the indemnity, or the payment for losses, exacted from China after the revolt was later turned into a scholarship fund to enable Chinese students to study in the United States.

The Election of 1900

The election of 1900 found McKinley more popular than ever. Bryan, who was again the Democratic candidate, tried to raise the issue of imperialism. But its effect was limited by the fact that the United States was prospering more than ever. The “full dinner pail” became a McKinley slogan. The result was an easy victory for McKinley and his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt.

Assassination

On the afternoon of September 6, 1901, at a public reception in Buffalo, New York, President McKinley was happily shaking hands with his many admirers. Suddenly a man walked up to the President with a handkerchief-covered revolver in his outstretched hand. Two shots rang out, striking McKinley at point-blank range. While being carried to an ambulance, he pleaded with police not to beat the assassin. Eight days later McKinley died, and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in as 26th president. The assassin, Leon F. Czolgosz, was an anarchist—one who rebels against governmental authority. He was speedily brought to trial and sentenced to death on September 26. Czolgosz was executed in the prison at Auburn, New York, on October 29.

Amid great mourning, McKinley was buried in Canton, Ohio. Ida McKinley died in 1907 and was buried beside her husband in a great memorial tomb. Another memorial to McKinley was erected at Niles.

With the passing of McKinley the United States, too, passed from one era to another—from an era of internal growth and expansion to one of growing participation in world affairs.

Andrew Bryce

Author, Narrative History of the United States