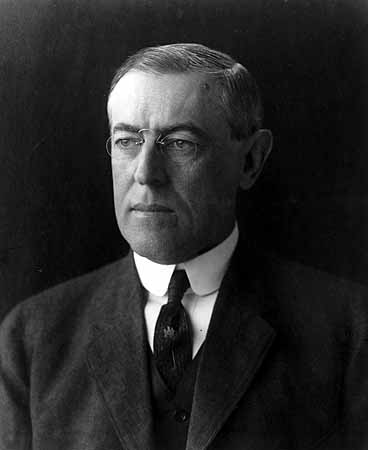

WOODROW WILSON

Biography

Woodrow Wilson holds a secure place among the great Presidents of the United States. Few if any chief executives have been more successful in dealing with Congress, which enabled him to win passage of a number of laws that laid the foundations of modern American public policy. Wilson also led the United States in its first important participation in world affairs, during and after World War I. He was, in addition, the man most responsible for the creation of the League of Nations, the parent organization of the present–day United Nations.

Teacher and Scholar

In 1888, Wilson accepted a post at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. In addition to his teaching duties, he coached the school football team. In 1889 he published The State, a textbook on modern governments. He acquired a growing reputation as a scholar, and in 1890 he left Wesleyan to become professor of jurisprudence, or law, at Princeton University.

The next twelve years were extremely busy and happy ones for Wilson, who quickly became the most popular lecturer on the campus. He wrote numerous articles and books to support his growing family and the many relatives who lived at the Wilson home. The best of these books was Division and Reunion, a history of the United States between the Andrew Jackson era and Reconstruction. The best known was a five-volume History of the American People.

University President

In 1902 the Princeton trustees elected Wilson president of the university. During his eight-year tenure, he became a familiar figure on the Princeton campus, striding rapidly across its grounds in traditional cap and gown. Although of only average height, he carried himself erectly. His strong jaw and rimless eyeglasses gave him a somewhat stern appearance, but beneath it lay a strong affection, particularly for family and friends.

His last two years were marked by a bitter quarrel with the dean of the Graduate School over the site of a new graduate college. Actually, the two men were fighting for control of the university itself. The dispute threatened to destroy Princeton. It ended only after an old alumnus died and left a large sum of money for the graduate college, naming the dean as a trustee of his estate, thus giving him power over the project.

Governor of New Jersey

Discouraged by the defeat of his plans, Wilson began to listen to friends who had been urging him to go into politics. One of his admirers was the editor of the magazine Harper's Weekly, who persuaded James Smith, Jr., a “boss” of the Democratic Party in New Jersey, to support Wilson's nomination for governor. Wilson agreed to the nomination, if offered without conditions. He aligned himself with progressive groups and won election in l910 by a large majority.

During the first months of his administration, Wilson, over Smith's opposition, won passage of a wide range of reforms. These included a system of direct primary elections, in which the voters nominated party candidates; a public service commission with power over the charges and services of public utilities and railroads; and an insurance system to help injured workers.

His accomplishments as governor made Wilson a national figure and a leading candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1912. The struggle for the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Baltimore was a long and heated one. Wilson's cause seemed hopeless at first, but he slowly gained support, finally winning the nomination on the 46th ballot.

The 1912 Presidential Campaign

In the presidential campaign that followed, two other major candidates contended for the office. The Republicans had renominated President William Howard Taft, who was an unpopular choice. Former president Theodore Roosevelt, who had been refused the Republican nomination, ran under the banner of his newly organized Progressive Party, better known as the Bull Moose Party.

Both Wilson and Roosevelt waged vigorous campaigns. Wilson called his program the New Freedom. It called for legislation to reduce the tariff, or tax on imports; strengthen antitrust laws; and reorganize the country’s banking and credit systems. Wilson won an overwhelming 435 Electoral votes to Roosevelt's 88 and Taft's 8. No candidate won a majority of the popular vote, but Wilson received a plurality of 42 percent. He carried a Democratic Congress into office with him

President

The Democrats had been out of power since 1897, and Wilson had to build an administration from the bottom up. To help him, he enlisted the aid of Colonel Edward M. House, a soft-spoken Texan whom he had met while governor and liked immensely. House would play an important role as Wilson's most trusted advisor and diplomatic emissary.

Wilson appointed the old Democratic leader William Jennings Bryan to the post of secretary of state, in order to ensure Bryan's support for his domestic legislation. Josephus Daniels, a newspaper editor from North Carolina, was made secretary of the navy in return for his support during the fight for the nomination. Most of the other cabinet members were appointed for similar reasons. The difficulty of finding experienced people placed a heavy burden on Wilson, who often had to do the work of subordinates because he could not trust them to do it well. This was especially true in foreign affairs.

The New Freedom

Breaking the custom of more than a century, Wilson appeared in person before Congress to demand fulfillment of the first Democratic campaign promise—reform of the tariff. As party leader, he used all his powers of persuasion to overcome congressional opposition. The result was the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act of 1913, which greatly reduced tariff rates and provided for a modest income tax, the first under the 16th Amendment to the Constitution. Next he won badly needed changes in the nation’s banking system and its currency under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which created twelve Federal Reserve banks to perform central banking functions. In 1914, he obtained two measures for more effective control of business—the Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act.

During 1916, Wilson obtained passage from Congress of even more ambitious legislation to promote social and economic welfare. Three of the measures were of particular importance: the Child Labor Act, which prohibited children under age 14 from working in factories; the Federal Farm Loan Act, which provided loans to farmers on easy terms; and the Adamson Act, establishing an 8-hour day for interstate railroad workers.

Mexico and the Caribbean

Wilson was also deeply involved in foreign affairs. Events in Mexico, then torn by revolution, caused him much anguish. He refused to acknowledge the dictator Victoriano Huerta, who had assumed power in 1913 after overthrowing the legitimate president, and in 1914 he sent the navy to occupy the Mexican port of Veracruz. Wilson's support for the constitutional forces helped to topple Huerta. But his recognition of the new president, Venustiano Carranza, brought him into conflict with a rival leader, Pancho Villa, who in 1916 led a raid against the U.S. border town of Columbus, New Mexico. In response, Wilson dispatched a cavalry expedition under General John J. Pershing against Villa.

Wilson also intervened, reluctantly, in the troubled affairs of Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. Between 1914 and 1916, he sent troops to the three countries to restore stability and protect U. S. interests.

Outbreak of World War I

Meanwhile, World War I had erupted in 1914 and quickly engulfed most of Europe. The combatants were the Allies, led by Britain and France, and the Central Powers, led by Germany and Austria-Hungary. The war created new and more difficult problems at the very time that Wilson was saddened by the death of his wife. He later met Mrs. Edith Bolling Galt, a young widow, whom he married in 1915.

Along with most Americans, Wilson wished to avoid being drawn into the conflict, but his policy of strict neutrality was difficult to maintain because of the nature of the war at sea. Britain used its naval superiority to blockade the Central Powers, and Germany responded with a campaign of submarine warfare against Allied merchant shipping. The United States found itself caught between the British blockade, which interfered with neutral trade, and Germany's undersea war. When the British liner Lusitania was sunk by a submarine in 1915, with the loss of more than 1,000 lives, including 124 Americans, Wilson sent the German government a strong warning, forcing it to stop the sinking of passenger ships without warning.

The 1916 Election

Wilson easily won renomination in 1916, campaigning on a platform of peace and progressivism. His Republican opponent was Charles Evans Hughes, an associate justice of the Supreme Court (and later U.S. chief justice). The election was extremely close, with California giving Wilson the neccessary margin of electoral votes to defeat Hughes—277 to 254. Less than 600,000 popular votes separated the two candidates.

Second Term

Wilson had offered himself as a mediator in the European conflict. In December 1916, he had called on both sides to state upon what terms they would be willing to end the war, but his efforts were rebuffed. In January 1917, Germany, in a desperate gamble, announced that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare, leading Wilson to break diplomatic relations. Finally, after it became clear that it could not be avoided, he asked Congress, on April 2, 1917, for a declaration of war against Germany, proclaiming that “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

As war leader, Wilson marshaled the country's economic resources and raised an army of more than 2 million men that helped turn the tide toward victory for the Allies in 1918. Even more important, he held out great moral objectives for peace, which he developed more fully in his Fourteen Points speech of 1918.

Peace Conference

Wilson headed the U.S. delegation to the peace conference in Paris, where he was hailed as a hero. The peace treaty with Germany, the Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, was a compromise between Wilson's idealism and the harsher demands of the other Allied leaders. One clause of the treaty provided for the creation of the League of Nations. Wilson was certain that U.S. leadership in the League would help heal the war's wounds, correct some of the treaty's injustices, and prevent future conflicts. Upon returning home, he presented the treaty to the Senate for ratification.

Struggle for the League

Although most Democrats and some Republicans in the Senate favored immediate approval, a group of Republicans, led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, strongly objected to the commitments Wilson had made concerning U.S. participation in the League. They would not agree to ratification unless changes were made in the United States'obligations.

Replying that such changes would cripple the League, Wilson refused. He then embarked on a long speaking tour of the western states to plead for public support of the League. After traveling 8,000 miles and delivering 40 speeches, he broke down from overwork. On October 2, 1919, he suffered a severe stroke that left him paralyzed on one side. He recovered enough to run the government but never regained his old powers of leadership. The result was defeat for the treaty when the Senate voted on ratification.

His Last Years

The Republican landslide of 1920, which elected Warren G. Harding to the presidency, ended any hopes that the United States would became a member of the League of Nations. That same year, Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 1919, for his efforts in establishing the organization.

After leaving the White House in 1921, Wilson retired to his home in Washington, D.C., broken in body but not in spirit. He never doubted that the American people would come to understand and share his vision of a world united for peace and progress. He died on February 3, l924, and was buried in the National Cathedral in Washington.

Arthur S. Link

Director of the Woodrow Wilson Papers, Princeton University

<<William Howard Taft | Biography Home | Warren G. Harding>>